The year of dying

A tribute to my cousin Joel and meditation for 2023 on deaths of many kinds.

By

In April, I posted this to Substack Notes:

Sometimes, death wins. My cousin Joel, who’s about my age and a nice guy (why is it always the nice ones), is dying (cancer). And today, as he begins hospice, we had to give up on our pear tree, as it’s finally succumbing to blight. There’s no cure for this cancer, nor this blight. Last year we saved the pear, or so we thought, and had nine fruits from its branches. My cousin got an “extra” year, too, but now it’s 2023, and Death comes to claim them both.

This year seems to have taken up dying as its prevailing theme, at least here at our house.

The business I launched seven years ago and grew to employ six writers at our peak is slowly dying. A company is not a person. But a small, family business, as ours was, has a certain life of its own, and when the people who made it what it is are let go, the death is palpable. We wrote dialogue for video-game characters for a living. Our voice actors gave each character speech. The laughter we shared on table reads, the spirit we breathed into tiny screen images—those had an energy, and that energy has now gone cold and dark. Dormant, like the earth in winter.

The business of dying, too, is serious. My cousin Joel and his wife kept birds, and in the final weeks of his life, he requested the birds be homed elsewhere so that he could die in quiet. It takes concentration and effort to leave this world, as I have seen in other people who are dying. My husband’s mother, when she left, had to work at it. It took everything she had to die.

But dying is not always quiet. This spring I raised five chickens from day-old fluffs to gangly, eight-week-old teenagers, at which point they were all killed. A friend who unlike me has many years of chicken raising behind her calls this phenomenon the “May murders.” It’s a springtime rush for everything to eat and feed its own young, often at the expense of someone else’s.

Fudge Pie, the runt, the one I’d bonded with the most, went first, of course, as this is a year that finds it amusing to take your favorite chicken. She’d slipped out of her enclosure and was wandering in the open garlic bed, likely oblivious to the danger, when the kite or hawk—I’m not sure which, as our urban neighborhood hosts both—swooped down and sunk its claws deep into her skull, breaking her neck. Mercifully, she must have gone fast. I came home from wandering a used bookstore, ignorant of the crisis facing my chickens, and found her still warm but gone from this world.

The others were not so lucky. One night, a slithy tove stole into their coop through the egg door—a posthumously-noted flaw in the coop design—and brutally slaughtered the lot of them. There was a struggle that left behind the culprit’s claw, ripped out and still clinging to a hunk of paw meat. So one of my flock, probably the leader, Queenie—who’d eyed me through a crack in that egg door the night before with a look of suspect derision—had extracted at least her pound of flesh. The scene that greeted me that fateful May morning was like something out of a slasher flick, with feathers and legs and pieces of my sweet chickie-boos strewn carelessly around the coop. I thought the tove, probably a mink, took one body away to feast on later, but then I found what was left of her, drowning in the water bowl.

When we raise livestock, we make a pact with them to provide for their needs and protect them so that they will in turn provide for some of our needs. My chickens held up their end of the bargain, tilling the soil, fertilizing it, and eventually, they would have given their eggs. I, in turn, failed them. That’s on me, a lesson for another go, if I’m so brave.

I’m an urban farmer, and I use the word farmer literally, as we are officially one of only two such farms in the St. Louis area. Due to more flexible size limits and use regulations, backyards like mine of just a quarter of an acre can now be declared a “farm.” This change might bring new life into farming, a dying occupation, or at least maybe that’s the hope. Fewer than one percent of US citizens are farmers, but it’s even worse than that sounds: “Farmers” are defined as principal producers, according to the latest United States Department of Agriculture Census, from 2017. “The term producer designates a person who is involved in making decisions for the farm operation,” says the USDA. So we’re not defining “farmer” as the person who owns the land, as I own this quarter acre, but in this somewhat amorphous category of “decision-maker,” which is more loosely and variously assigned.

My cynical mind, now attuned to so much decay, wonders if the relaxed rules for the farm designation isn’t just a ploy to make the dire picture of agriculture in these United States look less alarming. If your average urban small-flock chicken raiser can now don a pair of overalls and call herself a farmer, especially with government grants on the line, that paltry less-than-one percent number will surely go up.

This is my first real strike at farming, as I’ve lived in either suburbs or their cities proper practically all my life.

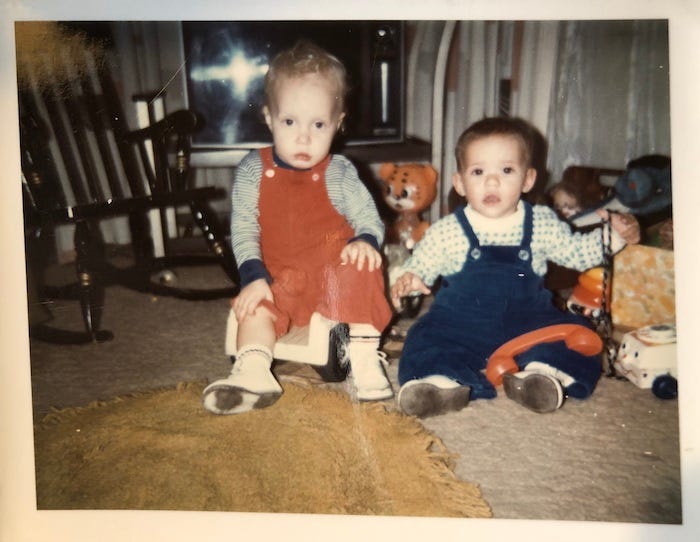

The only time I was ever a resident of the same small town where my cousin Joel lived his life, where nearly all of my cousins grew up and have lived their lives, was when I was just a toddler. While my father was fighting in Viet Nam, my mother and I lived there with my grandmother, and my mother babysat Joel, who was just a year older than I am. I have no memories of the time, but my mother says Joel was the nice one, giving in to my mischievousness.

My family visited that town, Rhinelander, a few times, staying for weeks or even a whole month once. I have memories of go-kart races and failed attempts to waterski. As a military brat whose family moved frequently, I never had extended family living around me, and we never lived in any small towns, not really. My father was always stationed at Air Force bases on the outskirts of mid-sized cities, places like San Antonio, Sacramento, Phoenix. Those few summers full of hordes of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins in Rhinelander stand out. The rambunctious, sprawling, squawking mess of it all, the spontaneous food fights and Fourth of July parades, live in my memory as the childhood I could have had, if my parents had been more like their siblings and simply stayed put.

Growing up one of four kids in a single-income family in the 1970s and 80s, thousands of miles away from the small town where both your parents spent their childhoods meant this: We only knew our cousins from these few trips—which I can count on one hand—and the school photos their mothers dutifully sent each year enclosed in Christmas cards. There were no long-distance phone calls, no Facebook chat messages, not even a one-second ‘like’ across time and space. But those obligatory school snapshots were the same as our own, the ones taken during group-photo day and delivered to you to bring home to your parents, a stack of identical mugshots to manually scissor apart, your name and age scrawled in ballpoint pen across the back. My siblings and I studied our cousins’ images, investigating them as if engaged in a game of spot-the-differences. Who had the misfortune to inherit our grandmother’s nose? Were so-and-so’s feet the same ungainly “banana boats” with which we’d been cursed? Whose hand-me-downs were we going to end up with next?

More importantly, were their lives shinier, happier, more exciting than ours? Would we have been better off if we could spend our winters snowmobiling and hunting for deer instead of losing quarters in pursuit of digital ghosts at the mall arcade?

When Joel turned half-a-century old, I sent him a funny happy birthday video, congratulating him on reaching that milestone before I did—just before, mind you, but still, he crossed the threshold first, and I knew he’d love a good-natured ribbing over that. The video was included in a compilation of such reels played during a private party at a movie theater in town. I pictured the extended clan there in force, along with friends whom Joel had known since birth, and in my mind’s eye it was practically Norman Rockwell-like in its pastoralism. An experience of his I oddly envied at the time, as if I had a right to envy someone with a cancer sentence.

When I’d first heard about his diagnosis, on his sister’s suggestion, nay urging, I called Joel, and we talked for a long while. It was a surprisingly pleasant conversation, and I was caught off guard by his attitude toward such a cut-short future. Frankly, I wouldn’t have blamed him if he’d expressed anger or a sense of betrayal. The Grim Reaper points his scythe at me before I’m ready, and I won’t be quite so accepting.

This was the first and only time we’d ever done that, talked on the phone.

When we were kids, you dialed long-distance only in the event of a death in the family. There was never a time when we cousins talked to each other via that wall apparatus, which was pretty much strictly reserved for adult use. Even after bonding with my cousins during that month-long trip, we simply went back to the casual monitoring of yearly class pictures, the groaning acceptance of hand-me-downs sent in a box via UPS.

As adults, once long-distance calls became more commonplace… Joel and I didn’t find the time or wherewithal to talk on the phone. I did speak with his sister on occasion, after a rare family-reunion trip to Rhinelander when I was in my forties granted us a grown-up, in-person relationship forged over one week.

I don’t think this estrangement is peculiar in any way, though. It’s all too common. America is largely a country of nomads, and we’ve long mourned and moved past the death of our family units and small-town communities.

I did not call my cousin this spring when I became aware that he was nearing the end. Something about it didn’t work, no matter his sister’s prodding this time. He had not kept up our correspondence after I’d initiated. In his flurry of travel on borrowed time, I was not one of the people he chose to visit. I thought I would give him the space to decide himself how to spend those final months, or at least that was my excuse.

More excuses: I had a lot of death on my hands, with the knowledge of Joel’s imminent passing, along with that pear tree, the chickens, and, of course, my own livelihood.

I have let all four of my staff go, and it’s just me here remaining. My husband, Tino, was one of the four, and he’s shifted to working in government grants again, the one seeming growth area in this year’s otherwise dead economy.

Punctuating Tino’s job search: a health scare. While Joel was engaged in the tough work of dying, I rushed Tino to the E/R, took him in for a procedure done under full anesthetic, and found myself completing what little work I had left on a laptop in fluorescent-lighted waiting rooms.

There was a flat-tire crisis in there, too, and a bizarre plague of insects whose bites swell, fester and ooze, and then turn black, all while spiking a fever, at least if the one bitten is my husband. Because 2023 wants you to know it’s not messing around, and everything’s fair game.

If the year of dying has taught me anything, it’s that we live the lives we’re determined to, and there are no take-backsies. As soon as Joel passed, I regretted that decision not to reach out to him for another conversation. But I also felt the sting of a larger missed opportunity, especially when his sister told me Joel had felt persecuted over politics in his social group.

A staunch conservative, he’d shown up at a Halloween party wearing a costume that apparently “triggered” his liberal friends, who decided then to drop all contact with the man. It angered and saddened me that the political divisions our leaders have taken great pains to sow had been a factor, as his sister believes, in metastasizing Joel’s cancer, which attacked and ate away at his gut. While I’m no self-proclaimed conservative, and I spent most of my adult life identifying as a liberal progressive, the past few years have made me further question everything I’ve ever believed in. That road of re-evaluation and questioning is one I’d been inching down even before the 2016 election.

So I wish I’d talked politics with Joel. Chances are good we’d have agreed on a great many things. Now I’m just sitting here, with one less potentially like-minded person in my life, surrounded in my liberal burg by the same kind of folks who take deep offense at Halloween costumes.

My clan itself is slowly dying, too, and that’s something else with which we must reckon. Joel is the third cousin on my mother’s side, all white men, to die before his parents. The other two didn’t even make it to middle age. When I divorced in 2009, I changed my last name to Brunette, my mother’s maiden name and the name of my matriarch, Alveda “Pete” Brunette. I did so in part to honor my family’s young men, cut down in the prime of their lives. It’s a Scottish name, of the House of Burnett, whose motto is “Courage flourishes at a wound.” If years had a motto, that one would fit 2023 perfectly.

My mother’s generation, the Boomers, expanded the House of Brunette exponentially, but my Generation X cohort is seeing it contract. Take Joel’s family. He did not have children, though he was married, and his brother is single and childless. His sister turned to adoption after a long and ultimately forfeited fertility battle. So his parents’ biological line ends here unless Joel’s brother shifts into marriage and family, not to put any pressure on him or anything… My own nuclear family didn’t fare much better, as my sister is the only one out of four siblings to birth children. While I’ve had a huge influence on my stepson, and of that I’m proud, he carries none of our Brunette genes into the future.

The morning my cousin died, at the very moment he passed, in fact, I was out walking. I had just taken a class on how to tune in better to the sounds of nature and interpret the behavior of wildlife. I’d signed up for the class in January’s optimistic delirium that this would be a kind year, a year in which a person could simply learn a little more about nature. After all, we’d just been through three years of hell, so things could only go up, right? What a fool I’d been.

Because of that nature class, I noticed something out of the ordinary, something I previously would have ignored: It was not the dulcet tones of cooing doves or the soft rustle of a squirrel slipping through brush but the shrieks of birds issuing alarm calls.

A hawk flew back and forth over a backyard nearby. I wandered over, peering through the vegetation and fencing carefully. I didn’t want to trespass into the yard, so I could not see what bird made this noise, but then I heard something different emerge from the alarm calls. The bird was dying, slowly, and it protested this fact, with all of its being, with the full strength of its voice. Maybe it was the hawk’s own young, in trouble, but I’ve since read that Cooper’s hawks, which are common here and increasing in number, primarily target other birds as prey. So more likely it was another bird, which the hawk was making its meal.

There was nothing for it, as this is the cycle of life, and mine is not to interfere with something so far beyond my control and comprehension. The sounds of a little thing dying are hard to hear, so I left. I went to a tree I often visit in a strip of woods. I held onto its trunk and wept.

I thought about my cousin and how he requested his pet birds be removed from the home there at the end. Maybe he wanted those birds out of his house because they were too much life to have around when you’re giving up your own.

I wrote this essay over the summer, when I was thick in the soup of loss. But I held off on publishing it here, as while true, it seemed maybe too dark for public consumption. It’s also very personal. While I can talk about my health, my garden, and my work as a writer with honesty and transparency, the rest is a valley further to travel.

Joel loved holidays, and the more American the better, so for Thanksgiving his sister hosted a huge gathering of family and friends, and they set a plate for Joel.

This weekend, as I’d mentally prepared to finally post this essay here, I walked in that same strip of woods, and my thoughts turned to Joel and the place made for him at dinner. Just then a little brown bird, all on its own, attracted my attention with its strange call. Distinctly addressing itself to me as I sat on the sole bench in these woods, it perched on the limb of a downed tree and sang out, earnestly, eyeing me the whole while. I smiled and watched and felt my cousin’s presence there in the bird. It was a Carolina wren, my sources tell me, and its call is described this way: cheery-cheery-cheery!

I don’t think Joel wants us to be sad about losing him anymore.

I am so grateful that your post about homemade yogurt randomly showed up in my Substack today as I got to read this amazing post as well. I’m looking forward reading more about your journey into mini homesteading. You’ve already inspired me to resurrect my old garden on my quarter acre lot.

What a touching, deeply sentimental story of life and its many challenges. It touched me to the core. I can relate to so many of your Experiences and the way they were impressed upon you. I too often retreat to the forest finding solace under the trees. When my dog died a few years ago of cancer we buried him under the big oak by the gate to the garden it was his favorite place to sleep the hot summer days away. While I was sitting by his grave a cardinal came and perched on the fence just watching me. In the following weeks and months this cardinal showed up everytime I was outside and would flit around over the grave. Stop to watch me and sing out. If I didnt stop to sit quietly and observe him he would fly back and forth over my head and land on the arm of the chair next to me or the beam across the pergola. I began to think that he was actually a messenger for my dog. After doing some research on cardinals I found that legend has it that indeed Cardinals are messengers from those we love on the other side.