Solving the mushroom mystery

With a little help from two fierce fungi experts.

We’ve had dry years and wet years since we bought this place in 2017, and the mushrooms definitely prefer it wet.

Twenty nineteen in particular drenched us here in the Midwest. That plus having mulched over a great deal of our backyard with wood chips—creating a conducive environment for fungi—kicked off the first of our mushroom mania, putting my husband and me on a quest to learn more about them.

To that end, I reached out to two mushroom mavens—Ellen King Rice, wildlife biologist and writer, and Maxine Stone, author of the guidebook Missouri’s Wild Mushrooms—for help learning how to find and eat wild fungi. They taught me how to safely forage for wild mushrooms, a skill I’ve developed and honed on my own since then. It’s a practice no one should take casually, at least if you’re looking to eat them.

For my mushroom mavens, first I compiled images from backyard foraging as well as from walks in the woods. Then I checked in with them for some IDs, adopting their recommendations and learning from their advice along the way.

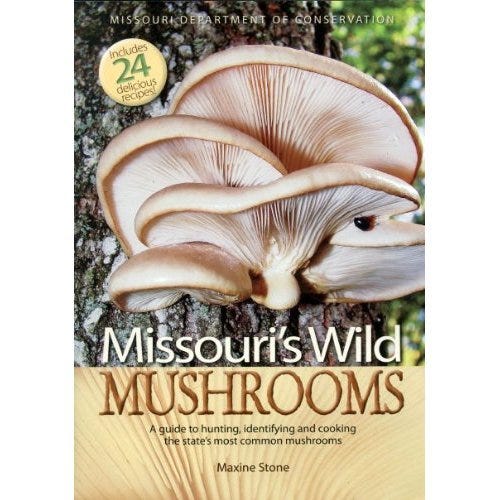

One of Ellen’s tips right off the bat was to get a good field guide, and Maxine’s book Missouri’s Wild Mushrooms1 fit the bill. It includes 24 recipes for using common edible mushrooms found in Missouri—delicious-sounding dishes like candy-cap sauce and barley-and-blewit salad. That book and many others are published by the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC), the same agency that puts out the award-winning magazine Missouri Conservationist, where my article on gardening with native fruit trees appeared last month.

With this project, I had asked Ellen to stretch outside the Pacific Northwest territory she knows best as I explored the mycology of the Missouri river bluffs where I frequently hike and the quarter acre that is our little city farmstead. So Ellen offered to focus on providing general biology insight and ID tips instead of specific IDs. When Missouri’s Wild Mushrooms didn’t yield a perfect ID, Maxine herself filled in any gaps.

Here are our conversations set as a Q&A. At the end, I’ve also compiled a list of easy steps to take when foraging for fungi on your own.

Lisa Brunette: Let’s start with the photo at the top of this post. I believe that marshmallow fluff-meets-wart stuff on top, paired with the bright orange cap, signal the poisonous amanita. Am I right?

Ellen King Rice: Some mushrooms begin growing inside an egg-shaped “leathery” sack. As the mushroom pushes up, the sack breaks apart and becomes blotches or spots on the new mushroom’s cap. The “warty” cap and the “egg cup” base are indeed hallmarks of the amanita group of mushrooms. Some of the amanitas are terribly poisonous. Some are psychoactive. A few are edible. Which leads us to the number one rule of mushrooming:

Don’t eat fungi until you are an absolute first-class champion at identifying the genus and species you are hunting.

But mushrooms are not nuclear waste or some spy-novel deadly dynamite. You won’t be poisoned by a mushroom if you photograph it or handle it!

LB: Ah, so that’s where the “wart” comes from; fascinating! And thanks for the balanced approach to identification. I assumed all amanitas were poisonous, so it’s interesting to hear that some are actually edible. Still, the risk is pretty great, so I for one wouldn’t eat anything that looks like this. Better to admire its remarkable orange hue.

After more research, I can confirm this is an iconic amanita, most likely muscaria, although iNaturalist says it’s Amanita cesarea. Most of the photos I’m finding of cesareas don’t have the white flecks of fungus on top, though, so I’m going with Amanita muscaria, or fly agaric.

According to the MDC, amanitas account for 90 percent of mushroom-related deaths. In Missouri’s Wild Mushrooms, Maxine lists the Amanita bisporigera, or “destroying angel,” as the top poisonous mushroom to avoid in Missouri. “Ingesting one cap of a destroying angel can kill a man,” says the MDC.

Yeah, so fine to look at and even touch—according to Maxine, you can’t get poisoned unless you eat them—but I wouldn’t even think of tasting anything that looked remotely like either of these—amanitas are a no go.

Maxine says the “lookalike” mushrooms are where a lot of people can go wrong, too. She shows which ones to watch out for in particular. She also cautions against eating mushrooms you find in your yard or the wild first without consulting a mushroom expert. Where to find one of those? Here in Missouri, she suggests the Missouri Mycological Society. But lots of states have mushroom societies; here’s a full list.

Sticking with the color orange, as it’s one of my favorites, the next fungus is in keeping with that bold preference. What’s going on with this beauty?

EKR: This fungus as well as the next three lead us to the challenges of identification. Like Sherlock Holmes, we need to pay attention to a lot of details to know the entire story of “what’s going on.”

LB: I believe this specimen is a cinnabar polypore, Pycnoporus cinnabarinus, judging by the guidelines in Maxine’s book. It has no lookalikes—which aids in identification. Though beautiful, the cinnabar polypore is not considered edible.

If I had a sample, rather than just this image, I could make a spore print to lock in the ID, right?

EKR: The biggest “con” for field guides is that these books are often organized by spore-print color. You’re supposed to take a sample of the fungus home, lay a cap section on colored paper overnight, check the color of the dropped spores the next day, and then go to the correct section of the field guide to begin the identification process. Whew! Not always easy or possible, especially if there are pets or small children in the home. Pro: Sometimes one can page through the photos of the field guide and “bingo,” quickly land on a photo that looks just like our find (Keep looking! Sometimes many things are nearly identical!).

LB: Maxine walks readers through the process of obtaining a spore print in her book, and while you rightly point out how life doesn’t always provide the space for this step, it’s not that hard—basically setting the cap gills-down on a piece of paper and waiting anywhere from two to 24 hours for the spores to drop. Plus, as Maxine points out, “Your spore print may be a beautiful piece of art and even frameable.”

Next up is this incredible ‘tree condo’ my brother and I happened upon one day in the woods. By the way, check out all that velvety moss we’ve got here in Missouri. To me it rivals the Pacific Northwest—at least in early spring, when these were taken. By summer, it dries up pretty well, even when it’s wet. I think that might be due to the heat. But this is likely not enough for you to go on here.

EKR: I’ll give another tip for learning how to ID: Go on a mushroom-club outing. The pros are you’ll meet some nice people, and you may quickly learn half a dozen of the most common fungi in your area. The cons, however, are that the dogs need to stay at home, and not every outing may be kid-friendly. You’ll also be working with a group, so it may be slower or faster than you like.

LB: That’s a great idea and something I’ve personally never done. I’ve seen quite a few opportunities to go on birding walks with experts who can share tips, but I’ve never seen anything like that for fungus. I checked with Maxine, and she shared this:

The Missouri Mycological Society (MOMS) is very welcoming to everyone... especially kids!!! We love them. The web site is MOMYCO.org, and forays are listed under events... they are free and open to all. We also have an “experts” page. The folks listed will help with ID, and we also offer ID classes free to all members.

How could they not welcome kids with an acronym like MOMS?

So after consulting Maxine’s book and sharing the above image with her, we think very likely the fungus condo above is dryad’s saddle. Like the cinnabar polypore, this is another ‘pored bracket’ type of mushroom. These can grow both singly or in layered groups. This one looks very much like the dryad’s saddle, Polyporous squamosus, which is edible. But again, I’ll take a spore sample first before cooking this up if I encounter it again. Another good tip from Maxine is to keep a little bit of any mushroom you eat in case you need it for ID purposes in the event that someone reacts to it. Even if they’re safe to eat, some people are more sensitive than others.

Note all ‘fruiting bodies’ appearing aboveground are technically mushrooms; whereas, fungi grow mainly underground, so those really are mushrooms forming the condo.

The rest of the photos were all taken here in our own backyard. I should preface the first crop by letting you know we had a ton of bark mulch on our land, making use of the sheet-mulch method. So I think this curious flora was born of rotting wood chips. I’ve been calling them ‘spore pops.’ What are these strange, alien things, Ellen?

EKR: I feel completely confident about identifying these…