It's not easy being green

Green energy isn't going to magically preserve our current lifestyle.

By Lisa Brunette

As a followup to two previous pieces, first a review of the landmark environmental warning Limits to Growth and second, my take on it called “Welcome to the slowpocalypse,” I want to wrestle with green energy as a solution.

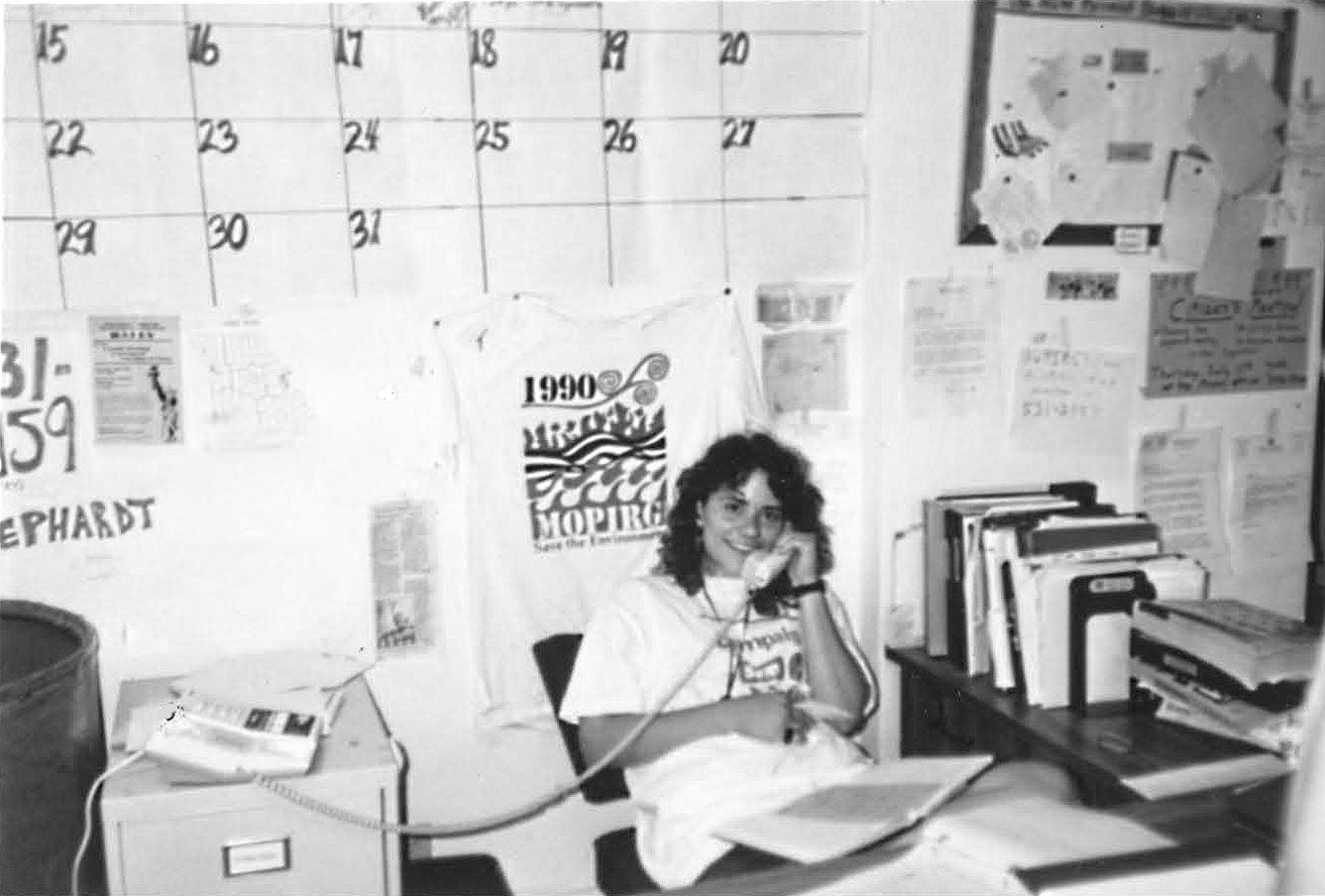

Let me preface with full disclosure: I have a history as an environmental activist. Back in the 90s, I chaired the board of Missouri’s largest (at the time) environmental organization, Missouri Public Interest Research Group (MoPIRG), and I used to run its summer canvass. Other green stints include a DC internship with the Union of Concerned Scientists and volunteer work with Forest Park Forever. These days, though, I focus on the 1/4-acre plot of land under my own control while trying to help out groups like Wild Ones, Seed St. Louis, Bat Conservation International, and the St. Louis Audubon Society. Outside of what I do with a spade, I’m pretty much an armchair activist now, but when it comes to green solutions, my heart has always been there.

So it’s with that in mind I carefully put forth the argument that switching to green energy isn’t going to work.

There. I said it. Felt like ripping off a Band-Aid.

This is really tough for me, but yeah, despite all my wildest green dreams of solar success and wind-farm fantasy, even I have to admit that renewable energy isn’t going to let us keep on the way we have. What I mean is, we can’t just unplug our current lifestyle from the socket of non-renewable energy and replug it into renewable energy and go merrily on our way like nothing’s changed.

Solar, wind, and other renewables are not a one-for-one substitute for fossil fuels. If they were, we’d already have transitioned 100 percent to those sources long ago.

But we haven’t, for several key reasons.

Remember EROI? As I’ve spelled out previously, energy return on investment is basically what energy you get out in return for the cost of obtaining a resource and processing it into a useable form. So all the work and cost to pump, refine, and transport oil, for example. Non-renewable energy sources such as oil, coal, and natural gas provide very high EROI, and that has built our modern age in a way that renewables could not.

No one’s explained the impact of fossil fuels on human society better than Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, known as the “father of the Navy nuclear program.” In a 1957 speech, he said

We live in what historians may some day call the Fossil Fuel Age. Today coal, oil, and natural gas supply 93 percent of the world’s energy; water power accounts for only 1 percent; and the labor of men and domestic animals the remaining 6 percent. This is a startling reversal of corresponding figures for 1850—only a century ago. Then fossil fuels supplied 5 percent of the world’s energy, and men and animals 94 percent.

This dramatic reversal in energy sources happened because fossil fuels provide a high return for the comparatively smaller investment of digging them out of the earth. EROI sounds like fancy-schmancy economic lingo, but the concept isn’t overly complex. And it’s key to understanding why we can’t just unplug from one source and plug into another. Rickover goes on to illustrate the high EROI of fossil fuels in vivid terms:

Man’s muscle power is rated at 35 watts continuously, or one-twentieth horsepower. Machines therefore furnish every American industrial worker with energy equivalent to that of 244 men, while at least 2,000 men push his automobile along the road, and his family is supplied with 33 faithful household helpers. Each locomotive engineer controls energy equivalent to that of 100,000 men; each jet pilot of 700,000 men. Truly, the humblest American enjoys the services of more slaves than were once owned by the richest nobles, and lives better than most ancient kings. In retrospect, and despite wars, revolutions, and disasters, the hundred years just gone by may well seem like a Golden Age.

The below list is from the paper “EROI of different fuels and the implications for society” published in the journal Energy Policy. You can see that oil, gas, and coal have EROIs of anywhere from 80:1 on the high end for coal to 67:1 for natural gas and 35:1 for oil. By contrast, wind, solar, and biomass EROIs are much lower, at generally less than 2:1.

What this means in terms of everyday life: Your solar panels aren’t going to be able to power your A/C, your refrigerator, your suite of electronic devices, and your washer and dryer all at the same time, especially not while you’re also charging your electric car. Take it from a couple who chose off-grid living in Canada—we will all have to make big sacrifices under a green-energy system. To quote from that piece, which you can read in its entirely over at the Late Prepper Substack:

You have to be willing to make some choices. It means modifying your behavior. We don’t have a fridge; we do have a microwave, but we only use it in the summertime when it’s really sunny. We don’t have a clothes dryer.

That comment about using the microwave only when it’s really sunny? It’s a hint at the other reason green energy can’t easily replace fossil fuels: It’s notoriously intermittent and unreliable.

The problem with wind power is it only provides power when the wind blows. The problem with solar is it only provides power when the sun’s shining.

Cue Kermit’s signature song: It’s not easy being green, when the clouds blot out the sun for days on end, or the wind dies down for the duration.

While battery storage can help with this issue, batteries can’t bridge a whole season’s gap, as our friends in Europe will find out this winter.

I often read a blog called Our Finite World written by Gail Tverberg, who comes at this whole thing from the unique perspective of an insurance actuarial. In a recent post, “Ramping Up Renewables Can’t Provide Enough Heat Energy in Winter,” she points out that

wind and solar production both typically drop in winter,

batteries cannot be scaled to store summer energy through winter, and

even hydroelectric power cannot fill the gap.

This last point is interesting to me and Anthony in particular, as one thing we note about living in Washington state is that it is largely powered by hydroelectric power and thus more securely clean and green compared to Missouri, which is powered mainly by coal-fired plants. The problem is that opportunities for hydro power have mostly been tapped already, so the likelihood of expanding that resource is low.

Much like the off-gridding couple I quoted earlier, Germans are already getting a taste of the drawbacks of a green lifestyle, with limits being imposed on when they can shower or even whether or not they can use hot water, for example. Many have argued that Germany and other EU countries have found themselves in the current predicament because of their shift to green energy. Germany’s commitment to green energy might have sounded great, but in practice, it has only increased their dependence on oil and gas from Russia.

So, am I saying we should just give up on green energy?

Of course not.

But we need to go into this with a clear-eyed view of its limitations. We will also need to make adjustments to our lifestyles. This one is of particular interest to me, as I have to set aside my frustrations with elites asking the rest of us to make sacrifices that they themselves are unwilling to make. This has already happened a lot during the pandemic, and we’ve seen it in terms of climate change as well. But I try to remember what’s in my own control and deal with that, and if I can better prepare for what’s ahead to meet it head-on, then I will.

In an upcoming post I’ll talk about ways we can plan for the coming winter, which according to the Farmer’s Almanac, is supposed to be a doozy.

Have you struggled with the limits of green energy?

At the end of the month, all paid subscribers will be entered into a drawing for a free paperback copy of Limits to Growth.

I am constantly stunned by how Americans can feel persecuted and denied when . . . they have a roof over their heads, potable water, indoor toilets, an abundance of food, transportation and at least some access to health care. We are a rich but unhappy nation. Living slimmer lives may not only be what our world can support, it may also help us remember what makes us happy -- often social connections, not a vast refrigerator.