Going home again, pt. 4: Please fence me in

A word or two about walls.

By Lisa Brunette

Ed. note: Today’s piece is part of “Going Home,” a regular series.

Walls are always acts of violence.

So said the playwright Eileen Cherry when I interviewed her for a theater magazine back in the 1990s. I thought the notion was profound at the time, so I included it in my profile of Cherry and her work.

But now I think it’s a profoundly illogical thing to say.

By her own definition, Cherry was committing violence every second of her life, if she lived in a house and drove around in a car that wasn’t either a sand buggy or straight out of The Flintstones. During our very interview, in fact, which took place inside a space defined by walls, the walls effectively holding up a roof to keep the rain off our heads, Eileen Cherry was committing an act of violence.

In our modern era, we tend to cast walls in a negative light, whether we’re talking about the border wall between the United States and Mexico or the metaphorical wall one might put up to shut someone out emotionally. But walls, fences, stockades—these structures have been used for millennia to keep people safe. Its synonyms are protection, fortification, enclosure, rampart, bunker. Human beings needed walls in order to survive. We needed them in order to define our tribe, to set up an enclosure around the people we chose to claim as our own, allying to bond with them and defend them against all threats, from the wolf at the door, or the enemy in sheep’s clothing.

But do we still need walls?

Yes, in fact, we do. We need them even more now that our tribes have been disbanded, leaving us at the mercy of faceless bureaucracies captured by monied elites. Note they still employ walls. From their gated communities to their enclaves staffed by private security to their workplaces locked behind keycard-accessible security doors, walls are very much a part of their daily lives.

Any gardener knows she needs to fence off the tasty carrots from the rabbits, the berries from the deer, the bird feeders from the bears. Chicken wire is a marvelous fencing material, one that’s designed to keep the chickens enclosed as much for their protection as your garden’s protection from them. If you live in a remote, rural area where the police are a long drive away, a fence might be your first line of defense against individuals who intend to do you harm.

In our human relationships, we often talk about possessing proper boundaries. These are walls that define where someone might enter into our lives, and where they are forbidden to trespass.

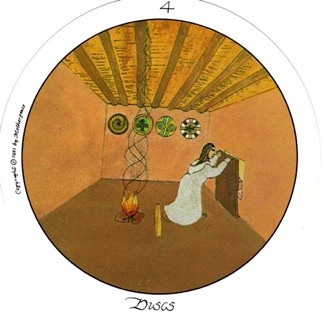

I used to regularly consult a tarot deck called Motherpeace, and a card I frequently drew was the Four of Discs. In the booklet accompanying the deck, this card is described as, “Gaining control of your doorway—who comes in and who stays out.” The image is of a young woman in an interior space all alone, in the act of shutting the door. The image held great meaning to me as one of four children in a lower-middle-class family; I had shared a room with my sister from the time she was born, two-and-a-half years after I was, and never had my own. Even in those first few years of life, my mother and I lived with her mother, my grandmother, while my father fought in Viet Nam. As Dad returned home and our family grew, we all simply doubled up. Our homes were small, crowded. Privacy was too high a premium.

Indeed. If you’ve ever had your privacy violated, as I have, you know deeply my meaning about a wall.

A favorite book from my childhood, one my sister and I agree helped define who we are, is Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden. That garden would never have been a delicious, cherished secret if it hadn’t been enclosed by a very high wall.

Without a six-foot cedar fence ringing the rear and side yards of the property my husband and I now own here in St. Louis, the energy of the place would sink into the asphalt parking lot next door. It would get whisked down the sometimes-busy road with every passing truck. It would be snagged by the freight trains and barrel down the tracks with them.

Dogs might wander through, wrecking the garden beds. Deer would most certainly feast. More than once we’ve spotted coyotes loping along the train-track corridor across the street, but they can’t get past our fence. Even black bears have wandered into our inner-ring suburb town, ranging further north from where they’ve been successfully reintroduced, in search of mates.

Without the fence, we’d have a bull’s-eye view of a row of apartment Dumpsters, our plants would brush up against a row of cars, and our garden would bleed into the neighbors’ yards on all three sides. Our backyard, where the bulk of our homesteading activity takes place, would be far less private—and less secure. Here I’ve been talking about wild animals gaining access, but what about the animal nature inside each of us? There have been three separate active-shooter incidents in our neighborhood since we moved here six years ago.

Most people cite Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall” for its overarching theme questioning the old adage, “Good fences make good neighbors.” But I’ll use it now to defend the utility of the wall, the necessity of it, its ancient wisdom.

In spiritual practice, one might first define the space by blessing it with water or sacred smoke, or drawing sigils in the air. Another kind of wall, entirely mystical and yet quite secure.

Our garden fence is possibly both: It’s of course made of wood and very real, but it also defines the space psychologically, metaphorically, spiritually.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

The link to the tarot deck is an affiliate link, so if you purchase the deck that way, Brunette Gardens might get a small commission, at no extra cost to you.

The fence is what keeps the deer and rabbits out of the garden. Nothing against the deer and rabbits, personally, but... they like my veg as much as I do!

I love a good wall, as long as it is good in both structure and purpose.